Understanding the source text

Understanding the source text is a key issue in any serious attempt at Bible translation. This article, the second in the “Translating the Bible” series by project translator Alan King, looks at some aspects of how the source text of the Gospels is approached in the Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat project.

What language?

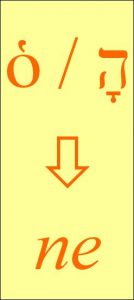

The original language of the Old Testament is Biblical Hebrew, except for a few passages in later books which are in Aramaic (a related Semitic language used as a lingua franca in much of the Middle East at one time). That of the New Testament is Koiné Greek, a later lingua franca of the Mediterranean area including Palestine. These then are our source languages, and the target language is Nawat. What do we need to know about each?

The original language of the Old Testament is Biblical Hebrew, except for a few passages in later books which are in Aramaic (a related Semitic language used as a lingua franca in much of the Middle East at one time). That of the New Testament is Koiné Greek, a later lingua franca of the Mediterranean area including Palestine. These then are our source languages, and the target language is Nawat. What do we need to know about each?

Regarding the first books of the New Testament (the Gospels), sometimes the issue of the language of Jesus is raised. Given the time and place in which Jesus lived as well as evidence from the NT itself (such as the Eli, Eli… phrase spoken on the cross), Jesus is assumed to have been a speaker of Aramaic, and the same would have been true of his disciples and other followers. Therefore, most of Jesus’ words reported in the Gospels were almost certainly uttered in Aramaic. We cannot conclude from this, of course, that Jesus knew no Greek, which was a language widely spoken in the Roman Empire to which Palestine then belonged. But even if Jesus spoke Greek it is unlikely to have been the language used to preach in, speak to the disciples and so on. Jesus probably knew Hebrew too. At the time Hebrew had largely given way to Aramaic as a common everyday medium of communication but was still understood and used by educated Jews, as today, as the language of prayer and in the reading of their holy scriptures. Jesus no doubt prayed in Hebrew and probably recited in Hebrew at least some of the prayers (or parts of them) that are cited in the NT.

“Jesus and the disciples are assumed to have spoken Aramaic.”

It is likewise to be assumed that Aramaic was the language in which the story of Jesus first began to be told and transmitted to younger generations, but no Aramaic texts of the Gospels are extant. As a written genre, the earliest known versions of the canonical Gospels are all in Greek and may have been originally composed in Greek, while drawing on earlier oral or written materials which in some cases no doubt would have gone back to Aramaic sources. It is therefore safe to say that there is an Aramaic substratum (and sometimes a Hebrew one) to the Greek Gospels. However, it would no doubt be going too far to suggest that the Gospels themselves were originally written in Aramaic and later translated into Greek. And in any case, in the absence of any actual Aramaic texts, the Greek documents are the most authoritative tangible sources available, whereas reconstruction of an Aramaic Urtext is, perhaps unfortunately, largely speculative.

The importance of Greek in Jesus’ time and subsequently is shown by the fact that the Jewish Bible (later to be dubbed by Christians the Old Testament) had already been translated into Greek by Jews living outside Palestine. This Greek translation, the so-called Septuagint, was more familiar to many diaspora Jews than the Hebrew prototype; this is the text that was most often directly quoted (or paraphrased) by the authors of the Christian Bible. Nonetheless, despite interesting evidence and archaisms in the Septuagint that sometimes throw light on the interpretation of the Jewish Bible, today Christians as well as Jews recognise in the Hebrew the most authoritative text, if for no other reason than that the Greek is after all a translation (and in this case we do have the original to refer to!).

Hebrew and Aramaic ought to be taken into account when researching or translating the New Testament as well as the Old, because Jesus’ words and teachings and the books of the New Testament all have originally Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts as a literary and cultural substratum (in OT quotations, references to or assumptions of Jewish concepts and customs etc.), and the Aramaic and Hebrew languages as linguistic substrata (being the languages in which many of the words and events of the Gospel occurred and were later transmitted, and out of which they were subsequently translated into Greek).

Which New Testament version?

The choice of a definitive source text of the Greek New Testament to be taken as a basis for the translation is not technically a translation issue, but in any case needs to be resolved for translation to take place. As early manuscripts of the Christian Bible were copied and recopied, voluntary or accidental divergences began to creep in, and when the text was later standardized and further replicated (and translated), the version that was adopted as authoritative was already contaminated by some deviations from the earliest text. For several centuries now, many generations of Bible scholars have been working assiduously to identify, reconstruct and reach a consensus on the historically most authentic variants, and their findings have progressively found their way into newer editions and translations.

Older translations, some of which have attained much renown in their own right (such as the Latin Vulgate or the English King James version), obviously can only reflect the knowledge available to scholarship contemporary with their date of composition (unless the translations are later revised, and then still only reflect what is known and accepted at the time of revision, of course). But this is a highly specialised field in which the position taken by the Ne Bibliaj project is a modest one; it is not for us to lead but to follow. The version of the Greek NT on which our translation is based is that which has been widely accepted by modern scholarly consensus for the past hundred years, known as the Nestlé-Aland (NA) version of the Greek New Testament (cf. the Wikipedia article here). Small incremental revisions have been published periodically, the current version being the 27th edition, referred to as NA27. In cases of doubt about the wording of the Greek text of the NT to be taken as the basis for translation, we follow the mainstream by referring to NA27.

“When the angel Gabriel greeted Mary in Luke 1:29, she was ‘troubled at his saying.’ But what did Gabriel say to her?”

For example, in Luke ch. 1 when the angel Gabriel appears to Mary to tell her that she is going to give birth to Jesus, according to the King James version of the English Bible he greets her with the words: “Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women” (Luke 1:28). This is a translation of the Greek version used by the translators of the KJV, but other Greek manuscripts lack the phrase “blessed art thou among women” at this point. The NA edition reflects the belief of modern Christian scholars that the verse probably did not originally contain that phrase, which was added later, and has simply χαιρε κεχαριτωμενη ο κυριος μετα σου, which (using the wording of the KJV) means merely “Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee”.

On the other hand, later in the chapter when Mary arrives at Elisabeth’s house, Elisabeth exclaims: “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb” (Luke 1:42). In this case scholars think that the words “blessed art thou among women” were in the text from the start; they were probably transferred from there into Gabriel’s greeting by an over-enthusiastic copyist. Here the NA edition reads ευλογημενη συ εν γυναιξιν και ευλογημενος ο καρπος της κοιλιας σου (similar to the KJV translation) and that is therefore what we follow in the Nawat translation.

The example discussed here, which may at first sight seem almost hair-splitting, turns out to be of slightly more substantial interest when we notice the verses that follow: “And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call his name Jesus (etc.)”. If the longer version of Luke 1:28 is assumed, then Mary might have been troubled (or puzzled, depending on how we translate διελογιζετο ποταπος ειη) at Gabriel’s saying to her Blessed art thou among women. But if Gabriel hadn’t said that, then the following verse can only mean either that she was troubled at his saying Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee or perhaps at the fact that an angel had spoken to her at all.

In literary terms, Gabriel’s next words cohere with his initial greeting (and Mary’s fear) in a subtly different manner (though not an earth-shakingly different one) depending on just what Gabriel is understood to have said the first time round. Granting the hypothesis of modern scholarship that the extra phrase is a spurious addition, we may speculate that perhaps whoever modified the text was trying to make the story more complete or symmetrical by having the initial greeting anticipate the whole explanation subsequently given. That might make sense dogmatically, yet in literary terms it makes for a lot of redundancy. And the literary aspect is pertinent given that the author was a competent writer (and a highly skilled one at that) in the middle of telling an exciting story.

Finding the meaning

But what are we to do when there is uncertainty about what those words of the Greek New Testament mean? Remember that the translator doesn’t only translate words, but a message; the message consists of both words and their meaning. The translator’s first task is to understand the meaning of the message.

But quite often words, especially in isolation, are potentially ambiguous or simply unclear. If the context resolves the ambiguity, the potential ambiguity can often safely be overlooked. If a passage or a phrase remains ambiguous in the original context and if that same ambiguity is easy to transfer to the target language text, it can even be left in, and the result considered a perfectly faithful translation. But some ambiguities are neither easily resolved nor transfer readily to another language.

“There is a long tradition of scholarly research into just about every word in the Bible.”

Fortunately, there is a very long tradition of scholarly research into the meaning of just about every single word in the Bible, and the translator must attempt to weigh up a range of opinions when considering passages that present difficulty. So much has been written about such passages that there is simply not enough time available to attempt to read everything thoroughly, but fortunately there is usually enough consensus among commentators to make that quite unnecessary. Guides consulted in the Ne Bibliaj project include up-to-date quality commentaries, and the classical older Bible commentaries and tools are also consulted at times. Naturally, various Greek dictionaries and grammars are also frequently referred to. It is also often instructive, in cases of doubt, to observe what has been done in other translations of the Bible, although we must consider when and according to what principles such translations were done and what source text might have been used in each case. Even if other translations cannot determine what ours should be, at the very least they do tell us something about earlier translation traditions.

Alan R. King