Target language resources

Exploiting the resources of the target language is the second key area in the Bible translation process examined in this series of articles written by the Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat project translator, Alan King.

Research, codification and systematization

The start of work on Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat was preceded by about five years of study, research, writing and language-recovery work on Nawat by myself in conjunction with IRIN and those who have worked with me in these projects. Work on the Bible translation project was not commenced until an adequate level of knowledge and language skill was achieved. In turn, my language work and that of my associates rests on the achievements of predecessors in Nawat language studies, of which the most important are Lyle Campbell’s study of the Nawat spoken in Cuisnahuat and Santo Domingo de Guzmán in the 1970s, and the study of the Nawat of Izalco through an admirable collection of oral texts by Leonhard Schulze Jena, carried out in the 1920s.

The start of work on Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat was preceded by about five years of study, research, writing and language-recovery work on Nawat by myself in conjunction with IRIN and those who have worked with me in these projects. Work on the Bible translation project was not commenced until an adequate level of knowledge and language skill was achieved. In turn, my language work and that of my associates rests on the achievements of predecessors in Nawat language studies, of which the most important are Lyle Campbell’s study of the Nawat spoken in Cuisnahuat and Santo Domingo de Guzmán in the 1970s, and the study of the Nawat of Izalco through an admirable collection of oral texts by Leonhard Schulze Jena, carried out in the 1920s.

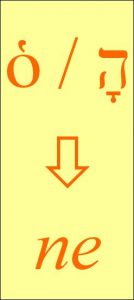

While knowledge is necessary, it is only as useful as it can be made by our capacity to access it; information that is stored away where we cannot get at it and draw on it does us no good. Indeed, writing was developed as a means of storing and transmitting data, and the reason for writing down the holy scriptures was to make the information they contain available to people in other places and future times. Writing is a conventional codification of language, the capacity of which to store and communicate texts efficiently depends on prior agreement on the rules and conventions according to which the codification is performed. Any language can be so codified through a set of appropriate conventions.

These conventions amount to what we call language standardization. Many languages have existed without writing in the past and some still do today, but it is generally recognised that developing and implementing a written form of a language strengthens its chance of survival in the modern world, giving it a better chance to avoid being swept away by the tendency towards uniformity and globalization. Hence language standardization, as a preliminary step towards the written use of a language, is linked in practice to the language recovery process.

“Great care has been taken in the Bible translation to ensure that the Nawat spelling used is functional, consistent and compatible with current trends in standard written Nawat.”

It is for this reason (among others) that the act of translating the Bible into Nawat and putting the Nawat Bible into writing constitutes a solid move in the direction of Nawat language recovery. Implementing a standardized form of written Nawat when writing the Nawat Bible is also a way of furthering the written codification process. Great care is therefore taken to ensure that the form of Nawat spelling and punctuation used in the Bible translation is functional, consistent and in line with other current attempts to standardize and implement written Nawat.

As a hitherto unwritten language, much of our scientific knowledge of the language is contained in or derived from transcriptions of initially oral texts from various sources. Collecting together such texts of different origins and tranferring their content into a standard spelling is part of the process of making the information they contain more accessible. Using modern technology we can go a step further by integrating the standardized corpus of texts into a computerized database where it can be used systematically through searches, concordances and more sophisticated language processing operations. Dictionaries or vocabularies compiled from a variety of sources can likewise be integrated into such systems, again improving the efficiency with which their content can be studied and used. Such techniques are now commonly used for larger languages, but since small languages have fewer human resources, the appropriate use of such techniques can be just as important.

Celebrating the language

Translating the Bible into Nawat is not a mere mechanical chore. It is an act of love and a festive event. When we produce a Nawat Bible we are celebrating the Bible in Nawat and also celebrating Nawat through the literary act of translating the Bible into it. Since the Bible is a unique and outstandingly beautiful cultural product occupying an exceptional place in world literature, we should expect a new translation of it also to be a work of striking beauty. The language in which this treasure is newly clothed should be finely worked to display both its own worth and the inherent value of the treasure it holds. In beautifying its content, the language itself will sparkle. By nurturing the linguistic vehicle we pay homage to the message it transmits while giving pleasure and satisfaction to the speakers who cherish their language.

“Translating the Bible into Nawat is at the same time a celebration of Nawat.”

We are in a somewhat special situation when the language is an endangered one. We all know from the experience of our own mother tongue, or any other language we know well, that no single individual can possess perfect knowledge of everything about a language. The language belongs to the community or the nation and its richness is divided up among all in joint ownership. Nobody can know everything about their language because there is too much to be known. How much more true must this be, then, when a language is endangered, its survival threatened.

For a language does not die all at once, but fades away over time; gradually fewer people speak it, and fewer learn it. Those who do manage to learn it hear it from others less and less; and since we learn a language by hearing it, fewer opportunities to hear their own language must mean that they cannot learn it as well, or learn as much or it. Thus, the closer to death a language is, the larger the proportion of its speakers who only know a small and diminishing part of the language they endeavour to speak, and who are in the tragic situation of forgetting their own language.

This is what language recovery means: it is for a people to recover the collective memory of their own identity, the sounds of their ancestors, the language of their people, which they are in danger, nay, in the process, of forgetting. That is why it is even more important that the celebration of translating the Bible into Nawat should be at the same time a celebration of Nawat, of the language’s beauty, of its life and of its wealth.

Keeping the language rich, idiomatic and diverse

This ambition will encounter obstacles and involves much hard work. Few speakers of any language have the specialized skills needed to translate well, and in a language with few speakers it will be correspondingly harder to find anyone in a position to even try. Furthermore, translating the whole Bible is a massive job and there may not be enough people with enough time to dedicate to it even in the unlikely case that they possessed the skills. In such cases, of which Nawat is one, responsibility for the translation may need be taken (not without misgivings) by a translator who is not a native speaker of the target language.

Rather than shy away from such a challenge in dispair, let us take stock of some of the ways in which a well-equipped, highly-motivated, non-native translator can respond. One of the most important objectives obviously must be to ensure the correctness of the language, but correctness alone is not enough. The target text should reflect the source text and the source text is not merely “correct”: it is literature. Besides, we cannot celebrate by serving only bread and water.

“The central message of the Magnificat isn’t the difference between psychê and pneuma; it’s that Mary is singing for joy!”

Much of the Bible is poetic, and poetry is itself a form of rejoicing, an extravagant “excess” in the use of words. A simple example: at the beginning of the Magnificat (Luke 1:46ff.), Mary’s hymn of praise, the future mother of Jesus is made to sing in Greek (we can imagine the original song having been sung in Aramaic): μεγαλυνει η ψυχη μου τον κυριον και ηγαλλιασεν το πνευμα μου επι τω θεω τω σωτηρι μου. In the King James version this is rendered: “My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour.” Now the only point I wish to make about this is a perfectly obvious one: that if this were not a song, a hymn or a poem, to all intents and purposes Mary would be repeating herself here, but it is a song. The key to translating this is not to take one word at a time and delve endlessly into the different shades of meaning to be read into “soul” (ψυχη) of the first line versus “spirit” (πνευμα) of the second, or “magnify” versus “rejoice”, or “the Lord” versus “God my Saviour”. If we do so we might miss the real message, which is that Mary is singing for joy.

So the Nawat of the Nawat Bible not only needs to be correct, it needs to be truly meaningful, expressive, flowing; capable of narrating and instructing and singing, of spreading its wings and taking flight; in short, of conveying the value and the sense expressed by the language of the original text. And to the extent that this can be done, the way to achieve it shares this with the process of artistic creation: that it involves much painstaking work, but that the final outcome aims to seem fresh, natural and spontaneous rather than attempting to flout any sophistication. That is the challenge.

As far as the target language is concerned in this process, the strategy involves intensive, systematic study of the available data on linguistic forms, constructions, meanings, and use. The most reliable and exhaustive compilations of Nawat vocabulary, supplemented by other terms attested elsewhere, are put to work as members of the active lexicon charged with the daunting task of re-creating the Bible as a Nawat text. Efforts are made to keep the text idiomatic by referring to the phrases and constructions that have been documented from native speakers. One of the most important tools is the electronically processed corpus of texts, consisting of transcriptions of past and present Nawat speakers.

“If a Bible translation sounds like all its parts have been written by the same individual, something’s missing in the translation. Is that important? Well, if the voice is a part of the message, yes.”

Last but not least, we exploit some documented aspects of natural internal variation within Nawat in order to be able to mirror, in the translation, the diversity of style and register found in the original texts. No reader of the Bible in the original languages can miss the existence of such stylistic diversity, yet all too often translations have tended to gloss over it. The Hebrew of Genesis sounds different from that of the Psalms, and the contrast between the Greek style of Mark and that of Luke is quite striking. These differences, together with differences of content or genre, contribute to the sense of identity, easily perceived in the originals and somewhat less so in some translations, that characterize the various books that make up the scriptures or their diverse authors. If all parts of a Bible translation sound like they have been written by the same person in a single voice, that translation is missing something. Is this important? It is if one considers that the “voice” (the medium) is a part of the message. Therefore the language of the Nawat Bible is characterized by a controlled diversity in an endeavour to reflect as fully as possible the original message and recreate the experience it offers.

Alan R. King